WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

When satellites and other space vehicles run out of fuel there are only two options – junk them or crash them into Earth. Now there’s a third option – refuel them in space and keep them running.

Love the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, read our codexes, or browse my blog.

Love the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, read our codexes, or browse my blog.

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), over 4,000 operational satellites are currently in orbit around Earth and that’s increasing substantially now that launch costs have fallen by over 99% in the last decade thanks to companies like SpaceX. Consequently, according to some estimates, this number is expected to reach as high as 100,000 by the end of this decade, including telecommunication, internet, research, navigation, and Earth Observation satellites.

As a result of all this not only will the presence of so many satellites create new opportunities, but it will also create even more hazards and possible space junk because, for example, when satellites run out of fuel, which they all do currently, they’re basically dead and have to be de-orbited and crashed into the oceans. Therefore they need a way to refuel in orbit, and now they have one …

The Future of Space, by futurist speaker Matthew Griffin

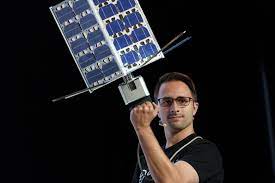

Needless to say the presence of these satellites will require a great deal of mitigation to prevent collisions, servicing and maintenance. For example, the San Francisco-based startup Orbit Fab is working to create all the necessary technology for orbital refueling services for satellites. To help realize this goal, industry giant Lockheed Martin recently announced that they are investing in Orbit Fab’s “Gas Stations in Space” refuelling technology.

The San Francisco-based startup was founded in 2018 by Daniel Faber and Jeremy Schiel, both of whom have strong backgrounds in the commercial space industry. Between 2016 and 2019, Faber was the CEO of Deep Space Industries (DSI), one of the leading companies currently developing asteroid mining capabilities. Schiel, meanwhile, was the vice-chair of the Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations (CONFERS), a consortium dedicated to fostering standards and best practices for satellite servicing.

As they state on their website, the company was founded to create “a thriving in-space market for products and services that support both existing space businesses (communications and Earth observation) and new industries like space tourism, manufacturing, and mining.”

Their first product is the Rapidly Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface (RAFTI), a fuelling port that will allow for orbital refuelling for satellites.

The RAFTI system is designed to extend the life expectancy of spacecraft by giving them the ability to conduct on-orbit refuelling. The system comes in two components: the Service Valve (SV) and the Space Coupling Half (SCH). The SV serves as a fill/drain system for ground fuelling and in-orbit refuelling, a primary docking adapter for attaching two spacecraft together, and a secondary servicing connection to facilitate servicing missions that use robotic arms.

The SCH is a double-action latch mechanism that supports both primary docking or secondary attachment of two spacecraft. According to the RAFTI Spec Sheet, the system measures 10 x 10 x .5 cm (3.9 x 3.9 x 0.2 inches), or 500 cm3 (30.5 cubic inches); has a peak power requirement of 10 watts (W); and can accommodate a flow rate of 1 liter (0.264 gallons) per minute (at an increase of 15 psi/m).

It can also operate at temperatures of -40 to 120 degrees Celsius (-40 to 248 degrees Fahrenheit) and pressures of 500 to 3,000 psi. Lastly, it can handle many types of propellant, including LOX/H2, water and alcohol, nitrogen, helium, xenon and krypton.

This summer, the RAFTI SV was flight-qualified after being launched to space aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. As part of an agreement with the Seattle-based launch service provider Spaceflight, the SV flew aboard Orbit Fab’s prototype Tanker-001 Tenzing spacecraft. This flight aimed to test the tanks, fuelling ports, thrusters, and rendezvous and docking systems.

The Tanker-001 Tenzing spacecraft is now in a sun-synchronous orbit (SSO) and carries high-test peroxide (HTP) fuel, a “green propellant, making it the world’s first operational fuel depot in space. Previously, Orbit Fab conducted a four-month testing program, launching a prototype tanker to the ISS in May of 2019. In the process, they validated their propellant feed system and became the first company to refuel the ISS with water.

Most recently, Orbit Fab announced that they had secured investments from two aerospace giants—Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman—both of which have a long history of manufacturing satellites for commercial, navigation and military applications. Chris Moran, the VP, executive director and general manager of Lockheed Martin Ventures, said in a recent press statement: “Lockheed Martin has a long legacy of investing in and developing servicing capabilities and their enabling technologies. This includes for military and commercial, large and small space systems. Our charter is to strategically invest in smaller technology companies focused on innovative technologies within our existing businesses, and Orbit Fab fits this criteria. We look forward to working with Orbit Fab and gaining access to their in-orbit refueling technology, an important component of space flight logistics that could help our customers address new and evolving threats.”

“This investment in Orbit Fab is one of several we have made that have created and supported innovative technologies and capabilities for on-orbit flexibility,” added Paul Pelley. “The ability to refuel a satellite on orbit is a critical component for our customers’ missions because it allows them greater maneuverability and can extend the life of a mission with replenished fuel.”

Pelley is the director of the Augmentation System Port INterface (ASPIN) program at Lockheed Martin Space. ASPIN is a docking adapter that the company will include in its LM 2100 combat satellite bus, which will allow for hardware and instrument upgrades in orbit. The adapter was designed to have plenty of open space to support refueling interfaces, such as Orbit Fab’s RAFTI port.

Earlier this month, the company announced that it had completed environmental testing with the Lockheed Martin IN-space Upgrade Satellite System (LINUSS), which will be launching for orbit later this year. Similar in concept to ASPIN, the LINUSS technology will demonstrate how small CubeSats can upgrade satellite constellations to expand their operations and extend their service lives.

This research is part of a larger effort to develop the necessary technology and tools to repair, refuel, and upgrade satellites in orbit. By extending their capabilities and lives, fewer satellites will become defunct over time, thus mitigating the possibility of collisions and orbital debris over time. After all, commercializing LEO means that we need to take steps to prevent the Kessler Syndrome from ruining everything!