WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

Centuries after they were first invented most lenses are still made of plastic or glass and Harvard’s new metalense will revolutionise the industry and let us make cameras and lenses that, eventually, will be just atoms thick.

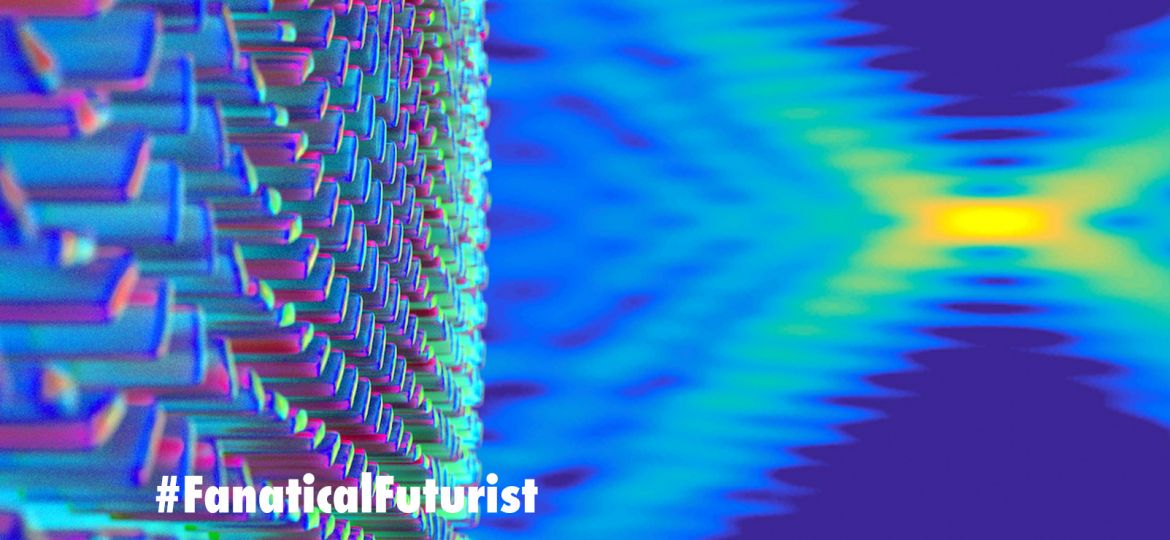

Metalenses, flat surfaces that use nanostructures to focus light, promise to revolutionise the world of optics by replacing the bulky, curved lenses we use today in optical devices, such as cameras, with a simple, flat surface, and, to put it in perspective, that would make smartphones the depth of credit cards possible, and revolutionise anything that uses glass lenses, even down to Virtual Reality (VR) headsets. Imagine it, no more bump on the back of your iPhone.

However, that said over the years metalenses have been limited to only being able to focus a narrow range of visible light meaning that they’re all but useless for only very specialist applications, but now a team of researchers at Harvard University have developed the first metalense that can focus the entire visible spectrum of light, including, crucially, white light, in the same spot and in high resolution. The research was published in Nature Nanotechnology.

The gallery was not found!

Focusing the entire visible spectrum and white light, which is a combination of all the colours of the spectrum, is challenging because each wavelength moves through materials at different speeds. Red wavelengths, for example, will move through glass faster than the blue, so the two colours will reach the same location at different times resulting in different foci. This creates image distortions known as “Chromatic aberrations.”

Today, cameras and optical instruments use multiple curved lenses of different thicknesses and materials to correct these aberrations, which, of course, adds to the bulk of the device.

“Metalenses have advantages over traditional lenses,” says Federico Capasso, who authored the research, “metalenses are thin, easy to fabricate and cost effective. This breakthrough extends those advantages across the whole visible range of light. This is the next big step.”

The metalenses developed by Capasso and his team use arrays of Titanium Dioxide Nanofins to equally focus wavelengths of light and eliminate chromatic aberration, and previous research demonstrated that different wavelengths of light could be focused, but at different distances, by optimising the shape, width, distance, and height of the nanofins.

In this latest design, the researchers created units of paired nanofins that control the speed of different wavelengths of light simultaneously. The paired nanofins control the refractive index on the metasurface and are tuned to result in different time delays for the light passing through different fins, ensuring that all wavelengths reach the focal spot at the same time.

“One of the biggest challenges in designing an achromatic broadband lens is making sure that the outgoing wavelengths from all the different points of the metalense arrive at the focal point at the same time,” said Wei Ting Chen, a postdoctoral fellow who worked on the project, “by combining two nanofins into one element, we can tune the speed of light in the nanostructured material, to ensure that all wavelengths in the visible are focused in the same spot, using a single metalense. This dramatically reduces thickness and design complexity compared to composite standard achromatic lenses.”

“Using our achromatic lens, we are able to perform high quality, white light imaging, and this brings us one step closer to the goal of incorporating them into common devices such as smartphones,” said Chen.

Now the researchers want to scale up the lens, to about 1 cm in diameter which would open a whole host of new possibilities, such as applications in Augmented Reality and VR.